Mayoral candidates puzzle

The wheel of politics is on the move again. In times like these, it’s almost news. On Sunday the primaries of the Democratic Party are held in Rome after last weekend’s ones organized by the center-left in Turin were a flop, due to the lukewarm popular participation.

Net of the mitigating circumstances from coronavirus, it is a data to dwell on. In Turin, PD candidate Stefano Lo Russo collected just over 4,000 votes (37%) out of about 12,000 votes overall. It was a much lower turnout than expected: about one fifth of the 2011 primaries, won by Piero Fassino. While in 2019 the Turin-based voters who participated in the election of the PD national secretary were double.

Lo Russo will challenge the center-right candidate Paolo Damilano in September, who a few days ago was one of the first civic candidates announced by the coalition. But at the moment the main fear of the PD leadership is another. That is, that the precedent of Turin is an ominous omen in view of Sunday’s vote in the capital.

In Rome, former Economy Minister Roberto Gualtieri will have no problem getting elected. He was favored by the withdrawal of the most formidable opponents while Carlo Calenda, leader of Action and rival in the race for mayor, has decided that he will not participate in the primary. He is also supported by the main national and local leaders of the party, those who still have a certain power of persuasion towards the militants.

The unknown factor is another and concerns more specifically what kind of victory will be that of Gualtieri. The Democratic Party has set the turnout at 50,000 voters. In 2013, the year of the primaries won by Ignazio Marino at the expense of David Sassoli and Paolo Gentiloni, there were 100,000 PD electors who showed up at the gazebos. Fear is that low popular participation could weaken Gualtieri’s candidacy, with the risk of compromising an electoral campaign that remains very open in view of the vote in October.

But if Athens cries, Sparta certainly does not laugh. In Rome the center-right has found an agreement on Brothers of Italy candidate Enrico Michetti, who has chosen emperor Cesare Augusto as his personal reference model. His opponents portray him as a “radio barker” and a nostalgic of Fascism. Others, however, underline that in the first round he will get the full votes of the center-right and that he will have his significant chances of conquering the Capitol.

The big question mark that agitates the Berlusconi-Meloni-Salvini alliance concerns the Brothers of Italy-League competition that is holding back the choice of center-right candidates for other relevant cities at stake. Such as Milan, Bologna and Naples. The only agreement is that on Calabria – where the current Forza Italia group leader in the lower house, Roberto Occhiuto, will run in tandem with League’s Nino Spirlì, who led the regional council after the late Jole Santelli.

Uncertainty is the result of the increasingly intense war of attrition between Meloni and Salvini for primacy in the coalition. The League has exhausted the driving force of a year ago and feels the breath on the neck of Brothers of Italy, which has been on the rise for several weeks now. In the meantime, opinion polls signal the slow but profound change that is altering the balance of power between parties.

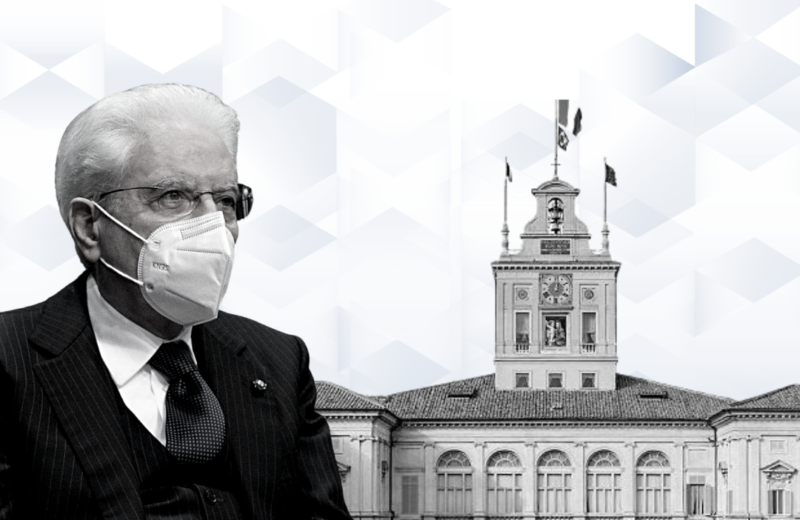

The animosity between the two main souls of the center right does not concern only the candidates-mayors but all the other main dossiers of the country’s political life. Salvini and Meloni are divided on almost everything from support for the Draghi government to institutional reforms, not to mention the hypothesis of early elections after the choice of the next head of State.

Meanwhile, the only one not to be affected by the climate of general uncertainty is Prime Minister Mario Draghi, after two excellent demonstrations of leadership at the G7 and NATO summits this week and who is now increasingly high in the ratings of Italians.