The numbers, economic and political, of Italy

The closing of the year is all about economics. Between the Budget Law, the ESM and the Stability Pact, Italy does the math, closes some accounts … and opens new ones. The reference is to the news that has altered the majority balance: the rejection in the Chamber of the European Stability Mechanism. After months of debate and surprise postponements, the proposal to ratify the reform of the European Stability Mechanism presented by the oppositions came to a vote in the Chamber and was rejected by part of the majority, with FdI and Lega voting against and Forza Italia abstaining. But the opposition was also divided, with PD, IV, Azione and +Europa voting in favor, AVS abstaining and the 5 Stars, as widely announced by Giuseppe Conte, voting against. Thus, our country confirms itself as the only one that did not sign the amendment to the so-called State bailout fund. This opens a (political) account with the European Union, because the new treaty will not be able to enter into force and will remain frozen for all the other 19 members of the Union who had already given the green light to the EMS amendment. Italy’s no could thus have political consequences by helping to isolate the country’s position in Europe.

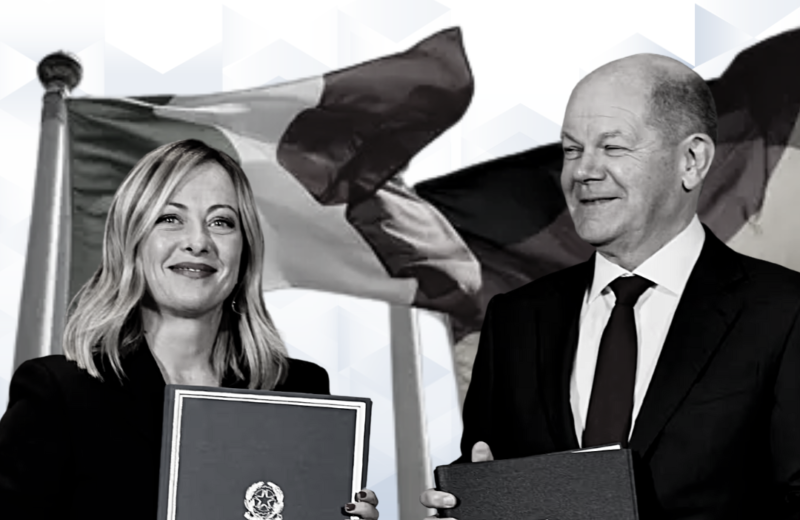

The other front of divergence in Europe is that of the Stability Pact. On Wednesday, the economy and finance ministers of the 27 European Union member countries unanimously approved a proposal to reform it. In principle, the rules under the Stability Pact are intended to make countries more likely to keep their public accounts in order by avoiding excessive borrowing and thus having negative spillover effects on the European economy. The rules of the Pact had been suspended in the spring of 2020 because of the pandemic, to give countries a way to spend billions of euros in aid to their citizens without too many constraints: they were not reintroduced thereafter and the measures have since been rediscussed. Particularly desired by Germany and France, however, the deal was met with disappointment by Prime Minister Meloni over the failure to automatically exclude investment from the spending calculation and discontent by Economy Minister Giorgetti, who nevertheless called the agreement “sustainable” for Italy.

In Rome, however, the spotlight is on the Budget Law, which is on track for swift approval by the end of the year. Despite a long stalemate in the Senate Budget Committee, in the end only a few amendments to the maneuver out of more than 2,500 submitted got the proverbial green light. The government thus confirmed the outline of the Budget Law 2024 that had been dismissed in the Council of Ministers, with the approved amendments correcting some issues related to pensions and the financing of the Strait of Messina Bridge. The measure thus will have a total scope of 24 billion of which 16 billion will be financed by means of an extra deficit; this is undoubtedly prudent legislation especially when compared to the promises made by the center-right during the election campaign. In spite of this, by virtue of the return of the constraints of the Stability Pact in the corridors of the Palace there is a sense of certainty that Italy will need a corrective measure to be put into practice in July 2024, a month after the delicate European elections.