State of emergency as an antidote to political instability

The government and its contentious parliamentary coalition are about to evaluate the most important dossier of this phase of the Legislature in the coming weeks or, at the latest, by the end of the year.

Citizenship income, revision of “quota 100” pension scheme, competition law, then tax reduction and finally the budget law. Without forgetting the many other reforms related to the implementation of the NRP. Topics that on the whole undermine the stability of the ruling coalition and consume the fibers of already weak and nervous parties, making the daily mediation work of Prime Minister Mario Draghi more and more difficult.

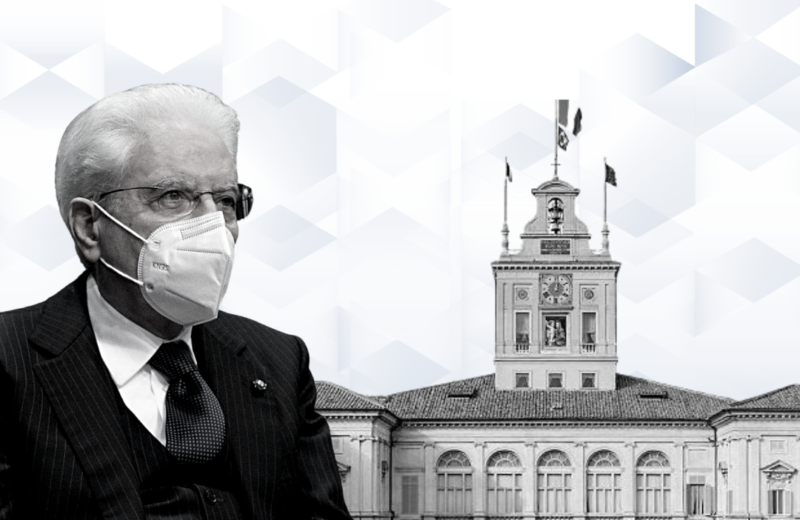

For these reasons, nine months after his (triumphal) entry into office, today the executive is showing signs of dangerous wear and tear. With the associated slowdown in government activity. The need to quickly close the most demanding dossiers is naturally linked to the Quirinale puzzle, which hovers like a boulder over the whole of Italian politics. To choose Mattarella’s successor, whose mandate expires on February 3, the electors will be called to gather in Parliament during the first week of January.

Mattarella’s stance against his re-election this week increased the confusion in the parties and, if possible, the alarm in the government. Given that regardless of the outcome of the Quirinale risiko, the new year will bring with it a harsh reality – early elections or natural end of the legislature in 2023 – the fear of Palazzo Chigi is that in both cases the parties will opt for the electoral campaign mode, to recover shares of their ancient consensus that was lost after the paralysis of recent years.

If this were the case, the most likely consequence would be a further slowdown in the execution of the government agenda, with the associated risk-paralysis in a year that promises to be decisive for the relaunch of the country and the execution of the recovery plan. Furthermore, on a general level, this would be the umpteenth confirmation that the Italian system tends towards stasis and “non-government”. The signs of these trends can already be seen in the difficulties experienced by the executive in these weeks.

Thus, the specter of political paralysis in view of the secular conclave in January combined with the (immediate) need to compact the ruling coalition explain why, in the meantime, the issue of the extension of the state of emergency has returned with force in the public debate.

Net of the restart of the infections and the fourth wave that is spreading in the Old Continent, it is evident that in the government’s calculations its extension represents the most valid instrument to guarantee the stability of Italy, protect the economic recovery and the health of citizens, but above all to impose another assumption of responsibility on the various souls of the ruling coalition in a time of disarray.

If it is true that the usefulness of the state of emergency lies in its ability to speed up interventions against the virus, it is no mystery that even in the parliamentary coalition that supports the government there are those who consider it an authoritarian act. For this reason, the choice will create discontent and controversy: for example, the head of the Lega Matteo Salvini in recent weeks took for granted the end of the state of emergency and also of the use of the green pass at the beginning of the new year.

For the malicious ones, it would also be a government ploy to remove the scenario of early elections and secure the position of the prime minister in view of the phase of political instability linked to the election of the head of state. Moreover, the news of the last few weeks sadly reminds us that the share of diehard no vax shows no sign of decreasing and that the street protests against the green certificate do not stop.