The Meloni government “at work”

The past week concentred around the theme of work, starting with the discussion that took place on Sunday between government representatives and the CGIL-Cisl-Uil Trade Unions to illustrate the measure at the centre of Monday’s Council of Ministers. The meeting, which lasted more than two hours, took place in an atmosphere of apparent cordiality; the Prime Minister focused on the need to have a “serious and constructive” dialogue with her counterpart on the challenges posed in particular by the labour sector and the NRRP. But the distance between the two worlds does not seem to have been bridged either in the substance of the issue or in the method of addressing it, and there was no shortage of controversy, especially on the following day: First of May, which the government has decided to celebrate by working. Meloni, on the one hand, described as “incomprehensible” the criticism of CGIL Secretary Maurizio Landini on the decision to convene the Council of Ministers on 1 May, thus coinciding with Labour Day. On the other hand, Uil Secretary Bombardieri lamented the convening of the trade unions a few hours before the final approval of the decree-law, commenting on the “irritation” that the government would feel at seeing the narrative of the first of May led by the trade unions.

Controversy aside, the work decree has been approved. A reform with a high symbolic charge that, certainly not by chance, the Prime Minister wanted to present on Workers’ Day to demonstrate how the government has “concretely” at heart the issue. The decree contains, among other things, a temporary reduction in workers’ contributions for medium and low incomes, with the aim to lower labour costs and increase salaries. The measure envisages raising by four percentage points the cut in the tax wedge, the difference between what is paid by the employer and what the worker receives as a salary, in order to increase the purchasing power, which has been considerably reduced by the price increases of recent months. In continuity with what had already been done by the previous Draghi government, the intervention on the wedge is probably the part of the decree on which the government is investing the most politically, despite the fact that the other two measures launched, the one on the replacement of citizenship income and the one for the renewal of fixed-term contracts over 12 months, are more incisive and, in any case, permanent. This is also because, in principle, there is a general consensus on the need to reduce the tax wedge given the high inflation impoverishing workers on fixed incomes. The tax wedge, in fact, represents a considerable burden both for companies, which have to face additional costs, and for the worker himself, who sees his net salary reduced by taxes and deductions.

However, the resources available to the government are rather limited and the measure is therefore likely to have a relative impact. Nonetheless, the decree was proudly claimed by Meloni, who spoke of the «most important tax cut on work in decades», only to then trigger a heated war of data with the opposition. All this while ISTAT announced consumer price estimates that in April rose again to 8.3% year-on-year (compared to 7.6% the previous month). The wedge cut then becomes an increasingly useful measure but, at the same time, with the rates recorded by ISTAT, also more complex to apply. It will therefore be up to the government to find the balance between the need to reach out to workers and the constraints of public finance and the current geopolitical context. Some points of reflection that leave Meloni’s strategy to fight inflation and support the world of work in abeyance, at least for now.

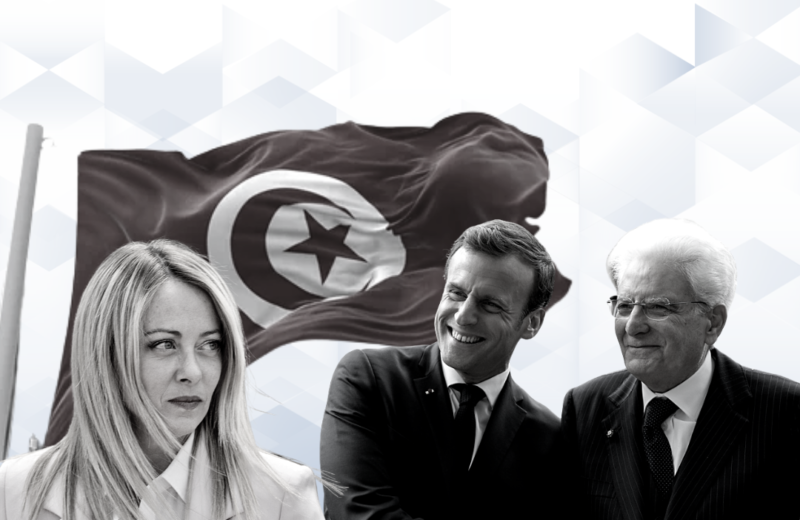

Meanwhile, a new diplomatic crisis seems to have erupted between Italy and France on the issue of immigration. After accusing the Italian government of “inhuman” management of the Ocean Viking ship in November, Thursday evening France’s Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin has caused a storm with his statement that “Ms. Meloni, at the head of an extreme right-wing government chosen by the friends of Ms. Le Pen, is incapable of solving the migratory problems for which she was elected. An unexpected attack that was followed by equally negative reactions from the Italian government. In fact, Minister Tajani announced that he had canceled his meeting with his French counterpart because “the insults to the government and to Italy uttered by Minister Darmanin are unacceptable: this is not the spirit in which common European challenges should be addressed”. In the diligent diplomatic work of rapprochement between Rome and Paris, this meeting should have been one of the stages in preparation for Meloni’s long-awaited trip to the Elysée Palace but, although the French Foreign Ministry hastened to declare in a note how it intends to work together with Italy, this hypothesis now seems further away than ever.