The fragility of Pax

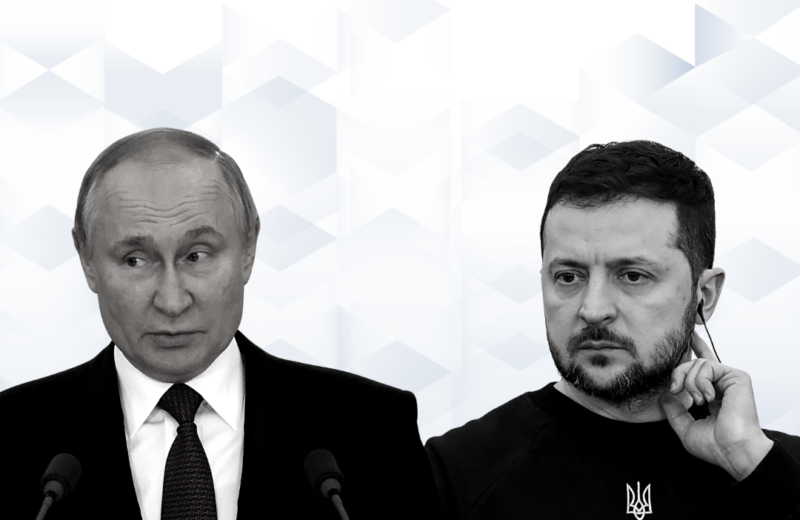

13th December. This could be the historic date of the opening of peace negotiations, in Paris, to engineer the conclusion of the conflict in Ukraine. This is the proposal that came out of the confrontation between Macron and Biden in Washington, a two-day event in which the French president essentially proposed himself as the true European interlocutor for the US, the role that former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi seemed to have carved out for himself before him. The Atlantic front proposes a ‘pax’ that is not unacceptable to Ukraine and on condition that Moscow is willing to a ceasefire. For its part, the Putin-Lavrov tandem has expressed an openness, albeit with some clarifications: from the identification of John Kerry as a possible interlocutor to the ‘piquant’ punctuation on the direct role that NATO and the US have played in the conflict so far. A signal that was interpreted by many as an orientation on the role Russia could play at the negotiating table. And Zelensky? The real news at the moment is his silence. The Ukrainian president has not commented on this diplomatic development. A signal of protest? Taste of defeat? An attitude that makes this attempt at a meeting aimed at peace very fragile, even though it is indeed the most concrete and realistic since the beginning of the conflict.

Italy, for the time being, stands by and watches. In the meantime, after the favourable vote on the majority motion in the Chamber of Deputies, the government approved the decree to send weapons to Ukraine for the whole of 2023. Not exactly those requested by Kiev (the missiles of the Samp/T system) but the Aspide, medium-to-long-range missiles, which are easier to surrender.

The vote confirmed the parliamentary turmoil of recent weeks. The majority showed no cracks by passing its motion compactly. The motions, similar in orientation, of the PD and the Terzo Polo also passed, thanks to cross-abstention votes and split votes. Parliamentary sources confirm that Calenda would have appreciated a vote by Fratelli d’Italia in support of his motion, but Meloni could not risk an internal crisis with Forza Italia, the party that more than the others has expressed disappointment at the winks between the centre-right and the Terzo Polo. Nevertheless, the trials of dialogue are going ahead, with the peace of the PD, which through the mouth of its secretary misses no opportunity to accuse Calenda and Renzi of being the government’s ‘crutch’.

After all, there is no doubt about it, Meloni is better off stabilising her majority as much as possible, if necessary broadening its base, because the next challenges will be very tough, especially those that see Brussels as a battleground. Indeed, the premier’s political week has been agitated. First of all, because of the assessed uncertainty of the achievement of the targets for obtaining the Recovery Plan funds. An issue that worries the ministers, who are aware that the new emergencies (rising costs, confusion of roles also due to the government turnover after the last elections) are making it difficult to keep to the schedule. Secondly, there is the bogeyman of the ESM, the European Stability Mechanism. During the week, the majority scored a partial success, voting compactly ‘no’ to the ratification of the bailout fund. This is a historic battle of Meloni’s, so the political price of a change of course would be too high. The position of Fratelli d’Italia, which tends to meet with the approval of the allies, has always remained the same: an eventual recourse to the MES would call into question the financial autonomy of the country, because the conditions for access to financial assistance under the pact are too stringent. But if Germany, the only country other than Italy that has not yet ratified the treaty, were to join the other 17 states that have already accepted it, Italy would bear a very heavy responsibility: its failure to ratify would bring down the entire treaty, whose entry into force requires unanimous ratification by the 19 countries concerned. With the vote in the Chamber of Deputies, Rome has taken its time. But time passes and makes the internal ‘pax’ more fragile and conditional.